by Caroline

When I am feeling nostalgic for my east coast childhood, I open up a bottle of my dad’s maple syrup. My kids have never experienced sugaring season; our school vacations never sync up with the less predictable week or two each year when the temperature dips below freezing at night but the sun shines brightly on the trees during the day. But I can tell my sons about tromping through the snow or mud to help my grandfather gather sap in old milk pails and bring it in to the farmhouse kitchen, which the boiling sap turned into a faintly sweet sauna. I can tell my sons how my dad digs out his old brace and bit every year just to drill holes in the trees; he has a good supply of proper sap buckets now, but I remember days when he would gather sap in anything he could hang from the spigot he put into the tree: a mason jar, an old yogurt tub. I share these stories as I pour syrup on their waffles, and for a moment my grandfather – gone these last 25 years — and my dad – 3,000 miles away — are present to us all, alive in my kitchen.

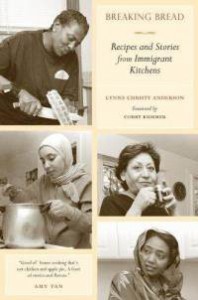

I love how food inspires stories, and how those stories build bridges across time or distance. I’m lucky that the bridges I build in the kitchen don’t have to reach too far, and they’re not too fraught. The grandparents who are gone can be remembered warmly for their long and fulfilling lives; the distance between my parents and me is not the result of economic or political hardship. But of course for many, that’s not the case, and those are the stories Lynne Christy Anderson gathers in her wonderful collection, Breaking Bread: Recipes and Stories from Immigrant Kitchens (University of California Press, 2010). Anderson is an English teacher in Boston, and in her teaching life began to meet so many immigrant cooks she wanted to learn both about their cooking lives in Boston and how also they were affected by their own or their parents’ move to the United States.

In each chapter, Anderson sets the scene with some background information about each cook. The chapter about Nezi begins, “There is nothing quiet about Nezi’s kitchen. In the midst of four chattering parakeets in a cage by the window and the whimpering of Kiki the dog begging for scraps, Nezi’s nine-year-old grandson, RJ, break-dances past the stove.” We meet Xiu Fen at the market, “in her element today, wheeling her carriage purposefully down the aisles of C Market, a large grocery store in Chinatown… Xiu Fen calls my attention to the things she likes to buy here: piles of leafy green pea tendrils, eggplant, water chives, Chinese celery and baby bok choy. There’s a certainty to her movements I don’t recognize. When I usually see her, bagging groceries at the large American natural foods market on the other side of town, she always looks a little tired.”

After each brief introduction, Anderson transcribes the cook’s own observations about his or her cooking life, offered while Anderson sits with them in the kitchen, shops with them in the local market, or even, in one case, forages for grape leaves in a local botanical garden. A fabulous contrast develops between the diverse voices — which are lively, weary, hopeful, discouraged — and Anderson’s own observant, keen-eyed introductions. The interviewees range widely in age, background, and economic standing, but as they talk about food, common themes emerge: the differences – in food, in childrearing practices, in gender roles, and in education — between the US and the home country; the power of food to carry you back to family and the familiar; and the importance of using food as a bridge to connect one’s children to a culture they may not have experienced first hand. As Anderson writes of her immigrant cooks, “For them, going back isn’t always so simple. But they can cook. And that brings home a little closer.” Or as Limya says, “It’s hard, because my kids don’t know anything about [my mother]. When I talk about [her] they just look at me like they’re confused. So when I cook now, I try to talk about her. When I do the hodra, I talk about how my mother would prepare it, how she’d cook the meat and onions with it, and how we’d all eat it together.”

I loved the discussion of specific foods and ingredients. Some of Anderson’s subjects find connections to other cultural groups in Boston, noticing that other immigrant foods are similar to their own. For example, Ines, from Cape Verde, observes that her katxupa is like a Cuban sanocho and comments, “When I talk with Caribbeans or Latinos, they make the same food we make – maybe slightly different – but it’s still beans and rice.” Others find that the home country persists in Boston, like the sisters from the Dominican Republic, Riqueldys and Magdani, who say “It’s not that different here; even the food’s the same. It’s like we live in a small Dominican Republic, because there’s so many Dominican people, and all the bodegas, the markets, are Dominican, too. Just the weather’s different. The way we eat, it’s the same here as it was there. We eat the flag. That means we eat rice, beans, and meat. That’s the flag, and Dominicans eat that almost every day.” But later in the same interview Magdani says, “The flour’s not the same… Some of the recipes we can’t do. A lot of the food back home is just better.” Sehin, from Ethiopia, similarly struggles to find the teff, millet flour, she needs to bake her injera. “You could get the teff before—we used to get it in Washington, D. C.—but it’s become very scarce. There was a guy in Idaho or Texas who used to farm it and sell it to restaurants, but I don’t know what happened to him.” And Shirley brings salsas and spices home to Boston every time she visits Costa Rica: “I gotta pack a whole suitcase of food I know I won’t have for a year or two.”

Each section offers a handful of recipes, and funny moments occur when Anderson tries to pin down specific amounts for recipes: “While I’m listening to Ana, I realize that Aminta has already begun to pour ingredients into the bowl for the quesadilla. “Cuanto?” (How much?) I ask, pointing to the bag of rice flour Aminta has in her hand. She shrugs and indicates with a finger approximately how full it had been before she started cooking. I copy the ingredients into my notebook as Aminta tosses pinches of salt, baking powder and small handfuls of grated parmesan into the bowl faster than I can write, and all the while Ana is still talking to me.” But Anderson’s interviewees have the same trouble. Soni, from India, says, “My husband started copying [my mother’s] recipes into this little book for us. He brings it to India every time we go. He makes her give him quantities and tells her to describe exactly what she’s doing. He’ll say, “No, don’t just say, ‘this much curry powder.’ Tell me exactly what you’re putting in.” Yasie, from Iran, teaches cooking classes and offers Anderson printed recipes: “She points to the recipes she’s printed for me, explaining that she’s noted how to replace the kashk if I’m unable to find it in my supermarket. I take them from her gratefully, the first time I’ve ever been handed recipes in the course of writing this book.” Barry gets cooking tips from his mom in Ireland via Skype, and Shirley calls her mom a couple times while making tamales to make sure she’s getting them right.

Like all cooks, these men and women make adaptations based on supplies and time. Aurora, who moved to Boston from the Philippines, is a professor of behavioral sciences and doesn’t always have time to cook everything from scratch. Anderson writes, “When she stops in front of the freezer section and grabs a box of platanos maduros, prefried frozen plaintains, she laughs: ‘This is my short-cut version. Anything short-cut I like to do. Besides it’s midterms now.’ She says she doesn’t feel guilty about not making everything from scratch, that her mother often did the same thing, because she, too, worked full-time. ‘Here’s another lazy thing,’ she says, tossing a box of prepared empanadas from the freezer into her basket.”

These cooks are nothing if not realistic, and they’re rarely sentimental about home – whether they’re discussing the home they left or the home they have made in Boston. Johanne, from Haiti, talks about the racism she encountered as a teenager new to Boston: “Every day there was a fight. They didn’t want us here. They’d say, ‘Go back to your country! Take the boat back where you came from!’ They called us boat people. I didn’t come on a boat; I came here on an airplane!'” Yulia, from Latvia, remembers how her father, a new immigrant to the US during the Vietnam war, was surprised to find that Americans could be as close-minded and influenced by propaganda as the Russians he had left behind. Sehin wants to live again in Ethiopia but feels cautious: “I would like to do something that would be useful, and I’d like not to have to be afraid that I would end up in jail if I said something. Even though things have improved, we’re still not there yet.”

But, Sehin concludes, bringing it all back to the food, “if I want to visit, one of the main things I could do is just go around and eat.” The pleasure in reading Anderson’s book, with its lively voices and rich details, is in feeling like you have shared a meal with her cooks. The words satisfy. And so I’ll conclude with one more voice, Ivory Coast’s Zady, who says, “you know, when I was growing up, whatever my mother made it was always the best thing of the day. I grew up eating her food, so it was the ultimate; there was never anything better. And I think when you go home and you eat your mother’s meal, that’s when you can say, the day is over and I can go to bed, because now I’ve been fed.”

Come back later this week for a post about some of the book’s recipes!

Learning To Eat » Archivio » Recipes from Breaking Bread: José’s Mother’s Sweet Cake

March 11, 2011 @ 11:34 am

[…] mother of José Carlos Ramirez, one of the folks Lynne Anderson interviews in Breaking Bread (click here for my review of the book). José left El Salvador in 2002, and now lives in East Boston with […]